Clinical environments generate vast amounts of operational data from electronic medical records, oncology information systems, PACS archives, and imaging and treatment-planning platforms. This data has enormous value for research, AI model development, and quality improvement. Yet pulling this data from production systems in a form suitable for analysis is exceptionally difficult.

The core challenge is architectural. Production clinical systems are optimized for real-time patient care, not for bulk extraction or analytical workloads. Large queries are throttled or deprioritized, exports are slow or unreliable, and research pulls routinely require manual workarounds. Even when data is successfully retrieved, it is rarely delivered in a format that can be indexed, searched, or reused. Metadata is inconsistent across vendors, identifiers change across systems, version histories are overwritten, and imaging data—particularly RTPLAN, RTSTRUCT, and RTDOSE—is deeply nested and poorly structured for research.

Compounding the problem, clinical data is distributed across multiple systems, each with its own APIs, storage formats, file hierarchies, and retention policies. Without a unifying ingestion architecture, institutions rely on manual exports, ad-hoc scripts, and brittle point-to-point integrations that cannot be scaled or repeated. Any new research request becomes a bespoke effort, and no two data pulls are ever exactly the same.

This creates the need for a repeatable, fault-tolerant ingestion pipeline—one that can reliably retrieve data from production systems, normalize and canonicalize it, preserve versioning and provenance, and index it in a form that research workflows, analytical systems, and AI pipelines can consume. Achieving this requires deliberate choices in workflow orchestration, storage layout, metadata extraction, and schema design.

This article presents one such architecture: a practical implementation built using workflow orchestration, canonical directory structures, systematic metadata normalization, and a research-optimized indexing layer.

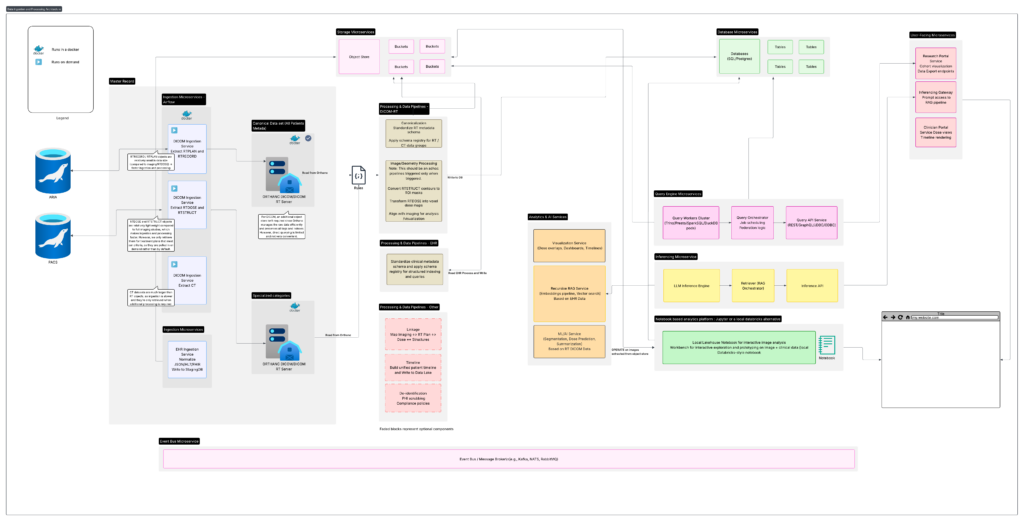

High-Level Architecture Overview

Building a reliable ingestion pipeline requires more than a set of scripts or scheduled exports. It requires a structured architecture that can operate continuously, tolerate failures and produce a consistent and research-ready dataset every time it runs. At its core, the design must separate extraction, normalization, canonicalization, and indexing into well-defined components so that each step can evolve independently without breaking downstream workflows. Each of these stages—extraction, normalization, canonicalization, and indexing—warrants its own detailed exploration, and in practice involves substantial engineering depth. This article does not attempt to cover every implementation nuance; instead, it provides a high-level architectural overview, offering a conceptual framework that future articles can expand on in greater technical detail.

The high-level architecture can be understood through the following core components:

Architecture Walkthrough

The diagram above represents a high-level architecture commonly used to design automated data-ingestion pipelines in clinical environments. While individual institutions differ in their systems and constraints, the overall pattern remains consistent: build a reliable pipeline that can extract data from production systems, normalize it, preserve structure and versioning, and make it accessible to researchers in a fast, repeatable, and compliant manner.

The following sections outline the major components and how they work together.

Data Sources: Clinical Systems, EHR Platforms, and Imaging Repositories

The architecture begins with the institution’s existing clinical ecosystem—systems such as ARIA, PACS, or other DICOM-based imaging archives. These systems hold mission-critical data, but they are not designed for high-volume or repeatable extraction. Imaging modalities provide the spatial, anatomical, and treatment-planning data necessary for research, but accessing them in bulk requires careful, incremental retrieval patterns that respect clinical load and system performance.

In addition to imaging systems, modern healthcare environments rely heavily on electronic health record (EHR) platforms such as Epic, Cerner, or Meditech. EHR systems store a wide range of structured and semi-structured clinical data: diagnoses, lab values, prescriptions, pathology results, clinician notes, encounter histories, and flowsheet metrics. While this information is invaluable for downstream research and AI development, EHR platforms are optimized for real-time clinical operations rather than analytical extraction. Large or repeated queries can slow down production systems, and access often requires compliance constraints, audit trails, and role-based controls.

Integrating EHR data into the ingestion architecture requires a similarly disciplined approach: controlled batch exports, throttled queries, incremental change capture, and strict separation between the clinical environment and downstream research infrastructure. When handled properly, EHR data becomes a powerful complement to imaging datasets—linking anatomical, dosimetric, and radiotherapy features with longitudinal clinical outcomes.

A disciplined upstream design across imaging systems and EHR platforms establishes a clear boundary between clinical and research operations, ensuring that all data enters the pipeline in a safe, consistent, and predictable manner.

Ingestion Microservices: Structured and Modular Data Retrieval

After defining the clinical and imaging data sources, the next component in the architecture is a set of ingestion microservices that manage how information is pulled into the research environment. Each microservice is focused on a specific data category—CT, MR, RTPLAN, RTSTRUCT, RTDOSE, or EHR-derived data—and operates independently within a containerized framework. This structure allows the architecture to treat each modality according to its own retrieval patterns and operational constraints.

A key purpose of this layer is to decouple clinical systems from downstream research workflows. Rather than allowing researchers or analytical tools to query production systems directly, all data movement happens through controlled, well-defined ingestion services. These services incorporate rate limiting, retry logic, batching, and validation steps to ensure reliable transfers without impacting clinical operations.

Each modality’s ingestion path can implement its own rules. CT and MR imaging require complete-series retrieval with integrity checks. Radiotherapy objects such as RTPLAN, RTSTRUCT, and RTDOSE need to be pulled together and preserved with proper versioning. EHR exports often rely on incremental change capture, capturing only what has changed since the last run. The microservice approach allows these rules to coexist without interfering with one another, keeping the system flexible and maintainable.

All ingested data lands in a raw, immutable staging zone. Nothing is transformed at this stage; data is written exactly as retrieved. This provides a reproducible baseline for downstream processing and eliminates the need to re-query production systems when rebuilding or validating the dataset. Alongside the raw files, each microservice records provenance metadata—identifiers, timestamps, system-of-origin details, and version markers—so every object can be traced back to its source.

In practice, the ingestion layer forms the protective boundary between clinical infrastructure and research workflows. By handling extraction through modular, containerized services with predictable behavior, the architecture ensures that downstream components receive clean, consistent, high-quality data without ever placing load on mission-critical systems.

To coordinate these ingestion services, the architecture uses Apache Airflow as the orchestration tool. Airflow provides a clean way to schedule ingestion jobs, manage dependencies, and ensure that each step runs in a predictable order. It also handles retries automatically, which is important when working with clinical systems that may slow down or limit requests. Because Airflow keeps a full history of every run, it becomes easy to monitor the pipeline, troubleshoot issues, and repeat past ingestions when needed. Using Airflow gives the ingestion layer consistency and reliability without adding unnecessary complexity.

Metadata Extraction Layer: Full DICOM Header Parsing Into JSON

After raw DICOM files are placed in the staging area, the next step in the pipeline is to extract the metadata directly from each file and convert it into a structured JSON document. This stage does not reorganize the data into a predefined schema or choose which elements are important. Instead, it follows a zero-loss extraction approach: every available DICOM header field—including vendor-specific and private tags—is captured exactly as it appears in the source.

This approach reflects the practical realities of clinical environments. DICOM metadata varies significantly across vendors, software versions, and modalities. Radiotherapy objects such as RTPLAN, RTSTRUCT, and RTDOSE introduce additional layers of hierarchy and complexity that do not map neatly onto rigid schemas. By capturing the entire header without filtering, the pipeline ensures that all potentially relevant information is preserved for downstream use.

Representing this metadata as plain JSON provides a clean, consistent, and portable format for future processing. New scanners or planning systems may introduce additional fields over time, but because the extraction process does not enforce a fixed schema, the pipeline naturally adapts to these changes without modification. This makes the ingestion step durable and easy to maintain as clinical systems evolve.

At this point, the extracted JSON metadata is not yet indexed or transformed. It simply serves as a structured representation of the raw DICOM headers, ready to be loaded into the indexing layer. This separation keeps the extraction logic simple and ensures that no decisions are forced prematurely about which fields matter or how they should be organized.

By focusing on complete header capture in a flexible JSON format, the architecture preserves maximum fidelity while setting the stage for powerful downstream indexing, searching, and analytical capabilities.

Indexing Layer: JSONB Storage in PostgreSQL With GIN for Fast Search

Once the full DICOM headers have been extracted into JSON, the next stage is to store these documents in a database optimized for flexible metadata and fast querying. PostgreSQL’s JSONB datatype is well suited for this role. It allows the pipeline to store each DICOM header exactly as it was extracted, while still enabling efficient search across both top-level fields and deeply nested structures.

A GIN (Generalized Inverted Index) is applied to the JSONB column, allowing researchers and downstream applications to query any metadata field—including private tags, vendor-specific attributes, or nested elements—without predefined schemas. This means that searches such as “all RTPLANs with a specific beam parameter,” “all studies from a given scanner,” or “all MRIs acquired with a certain sequence” can be executed quickly even at scale.

Storing the metadata in JSONB also creates a durable source of truth for the entire research data pipeline. Because the database contains a complete and accurate representation of every DICOM header ever ingested, it becomes possible to reconstruct or reinterpret the dataset over time. If new research workflows require different metadata fields, new normalized tables, or new domain-specific views, those can be generated directly from the JSONB source without modifying the ingestion process.

This approach avoids the rigidity of committing to a fixed relational schema too early. Instead, the architecture preserves maximum flexibility: the JSONB store supports exploratory research, rapid prototyping, analytics, and machine learning workflows while still allowing future extraction of structured tables if required.

Whether used directly for ad-hoc queries or transformed into highly optimized research views, the JSONB metadata index gives the system a powerful combination of speed, adaptability, and long-term stability. It ensures that the ingestion layer captures everything, and that future analysis layers can evolve without reworking the foundations of the pipeline.

Research Access and Transformation Layer: Direct Querying and Flexible Views

With all extracted metadata stored in PostgreSQL as JSONB and indexed with GIN, the system gains a powerful foundation for research access. At this point in the architecture, the metadata repository functions as a complete source of truth: every DICOM header from every ingestion run is preserved exactly as extracted, searchable at scale, and available for downstream processing.

Researchers and applications can interact with this data in two complementary ways—each supporting different stages of analysis and exploration.

The first is direct querying. Because JSONB fields can be searched efficiently using GIN indexes, researchers can run ad-hoc queries across any part of the metadata, including nested or vendor-specific fields. This is extremely useful for exploratory work, where a research team may want to filter studies by acquisition parameters, imaging vendor, sequence type, dose characteristics, or any other DICOM attribute. The database behaves like a structured catalog of the entire imaging dataset, without requiring a rigid schema. This flexibility allows teams to quickly answer questions or assemble datasets without building new tables or pipelines.

The second pathway is transformation into normalized or specialized views. Although JSONB provides flexibility, many downstream workflows—statistical analysis, radiomics pipelines, machine learning models, dose-volume studies—benefit from structured relational tables or curated domain-specific schemas. Because the indexing layer stores the complete metadata, these views can be created at any time and revised without altering the original ingestion logic. New normalized tables, materialized views, or summary layers can be generated from the JSONB source to support specific research objectives. As needs evolve, new interpretations of the data can be added without breaking the pipeline or re-ingesting the source.

Together, these two access modes—direct JSON queries and derived structured views—give the architecture both short-term agility and long-term adaptability. Researchers get immediate access to rich metadata for exploration, while larger programs and AI workflows can build stable, optimized structures tailored to their specific analytical requirements. The underlying JSONB store remains the authoritative source for the entire system, ensuring consistency across all layers of transformation.

Conclusion

This architecture provides a scalable, maintainable, and future-ready approach to managing clinical imaging data for research. By separating ingestion, metadata extraction, indexing, and downstream processing, the system remains resilient to changes in clinical workflows, imaging vendors, and research requirements. Researchers gain the ability to explore, query, and transform metadata with minimal friction, while institutions benefit from a pipeline that is stable, transparent, and simple to operate.

Clinical environments are complex and dynamic, but with a well-designed ingestion and metadata system, they can support rich analytical and AI-driven research without burdening production systems. The approach outlined here balances practicality with flexibility, offering a foundation that can grow alongside an institution’s research ambitions.